On the growth order of derivatives

special-functions complex-analysis real-analysisI have written Chinese account on the same subject in this January.

When we know $f(x)$ tends to some limit as $x\to+\infty$, there is a tendency to believe that the curve of $f(x)$ eventually becomes flat, so one reasonably conjectures $f'(x)\to0$ if $f$ is differentiable.

Unfortunately, this is not true because we can take

\[f(x)={\sin(e^x)\over x},\quad f'(x)={e^x\cos(e^x)\over x}-{\sin(e^x)\over x^2}.\]Therefore, we see that it is still possible for $f$ to oscillate violently when $x\to+\infty$ even if it has a limit.

However, we can still introduce additional conditions on $f$ to ensure $f'\to0$. Specifically, this happens when $f$ possesses a continuous and bounded second derivative as $x\to+\infty$.

Theorem 1: If $f\in C^2[x_0,+\infty)$ such that $f(x)$ converges and $f''(x)$ is bounded as $x\to+\infty$, then $f'(x)\to0$.

Without loss of generality, we assume $f(x)\to0$, so for all $\varepsilon>0$ there is some $x_1(\varepsilon)\ge x_0$ such that $\vert f(x)\vert<\varepsilon$ for all $x>x_1$. By Taylor's theorem, we have

\[f(x+y)=f(x)+yf'(x)+\int_0^y(y-t)f''(x+t)\mathrm dt.\quad(\vert y\vert\le x-x_0)\tag1\]By boundedness, there is some $M>0$ satisfying $\vert f''\vert\le M$, so we have

\[\vert y f'(x)\vert\le\vert f(x+y)\vert+\vert f(x)\vert+My^2.\]Take $x>2x_1$ so that for $-x_1<y<0$, there is $x+y>x_1$ and

\[\vert f'(x)\vert<2\vert y\vert^{-1}\varepsilon+M\vert y\vert.\]Setting $\vert y\vert=\varepsilon^{\frac12}$ gives $\vert f'(x)\vert<(2+M)\varepsilon^{\frac12}$ for $x>2x_1$, so $f'(x)\to0$.

When studying functions in general, we cannot always work with $f(x)$ that converges as $x\to+\infty$, so in this article, we will prove some generalizations of Theorem 1 that have much wider applications.

This article is based on a 1913 paper by Hardy and Littlewood1.

Generalization to upper bounds for $f'$

In this section, we assume $f\in C^2[x_0,+\infty)$ is real-valued with $x_0>0$ and define $\phi$ and $\psi$ by

\[\phi(x)=\sup_{x_0\le x'\le x}\vert f(x')\vert,\quad\psi(x)=\sup_{x_0\le x'\le x}\vert f''(x')\vert.\tag2\]Then by (1), when $x>x_0$ and $y\ge x_0-x$, there is

\[\begin{aligned} \vert f'(x)\vert &\le\vert y^{-1}f(x+y)\vert+\vert y^{-1}f(x)\vert+\vert y^{-1}\vert\int_0^y\vert y-t\vert\cdot\vert f''(x+t)\vert\cdot\vert\mathrm dt\vert. \\ &\le\vert y/2\vert^{-1}\phi(x)+\vert y^{-1}\vert\psi(x)\int_0^y\vert y-t\vert \cdot\vert\mathrm dt\vert \\ &\le\vert y/2\vert^{-1}\phi(x)+\vert y/2\vert\psi(x). \end{aligned}\]By the AM-GM inequality, we have

\[\vert y/2\vert^{-1}\phi+\vert y/2\vert\psi\ge2\sqrt{\phi\psi},\]where $\ge$ can be replaced with $=$ if and only if $\vert y/2\vert^2=\phi/\psi$. Because $\vert y\vert\le x-x_0$, we obtain the following generalization of Theorem 1:

Lemma 1: Let $f\in C^2[x_0,+\infty)$ with $x_0>0$ and $\phi,\psi$ be defined as in (2). If

\[4\phi(x)\le(x-x_0)^2\psi(x),\quad(x>x_0)\tag3\]then we have

\[\vert f'(x)\vert\le 4\phi^{\frac12}(x)\psi^{\frac12}(x).\quad(x>2x_0)\]The conclusion of Lemma 1 is very believable, but there is no reason for one to believe (3) can always be satisfied. To drop this condition, we use a geometric method.

A geometric argument

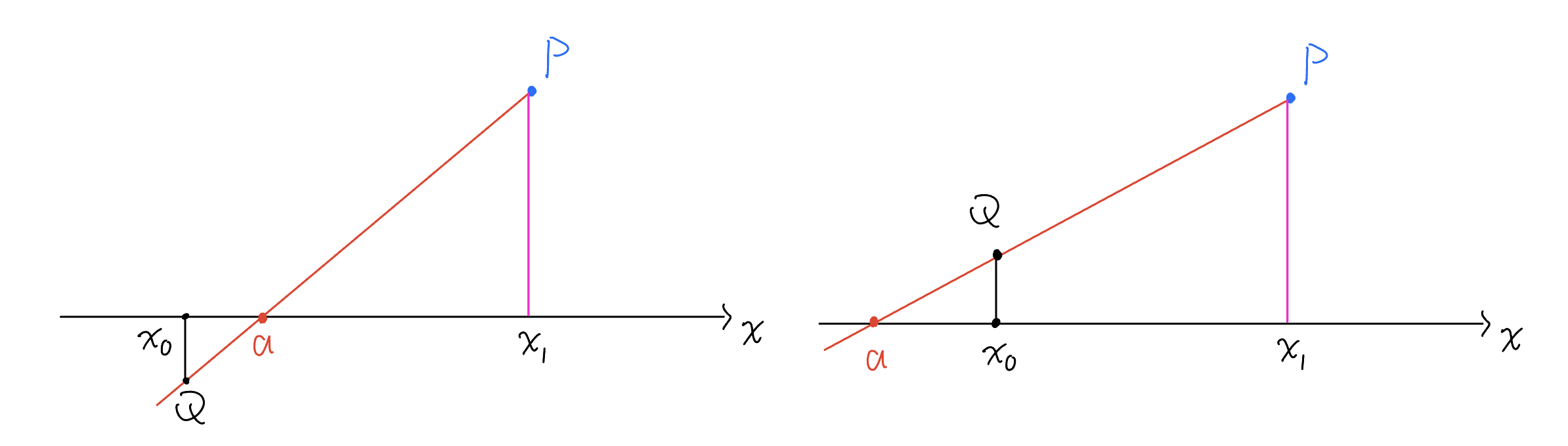

Since $f$ is real-valued, we can relate it with $f'$ and $f''$ by areas. Let $x_1>x_0$ be arbitrary. Assume without loss of generality that $y_1=f'(x_1)>0$. Label the point $(x_1,y_1)$ by $P$. Choose $y_0$ such that the line joined by $P$ and $Q=(x_0,y_0)$ has a slope of $\psi(x_1)>0$. Then by the fact that $f''(x)\le\psi(x)$, we have for $x_0\le x\le x_1$ that

\[f'(x_1)-f'(x)\le\psi(x_1)(x_1-x)\Rightarrow f'(x)\ge\psi(x_1)(x-x_1)+f'(x_1),\]which indicates that $f'(x)$ is above $PQ$ when $x_0\le x\le x_1$. For convenience, denote the $x$ intercept of $PQ$ by $x=a$:

If $x_0\le a$, then $f(x)-f(a)$ is no less than the area of the triangle formed by $a$, $x_0$, and $P$. In this case, we have

\[2\phi(x_1)\ge f(x)-f(a)\ge\frac12(x_1-a)y_1.\]Clearly, $x_1-a=y_1/\psi(x_1)$, so there is

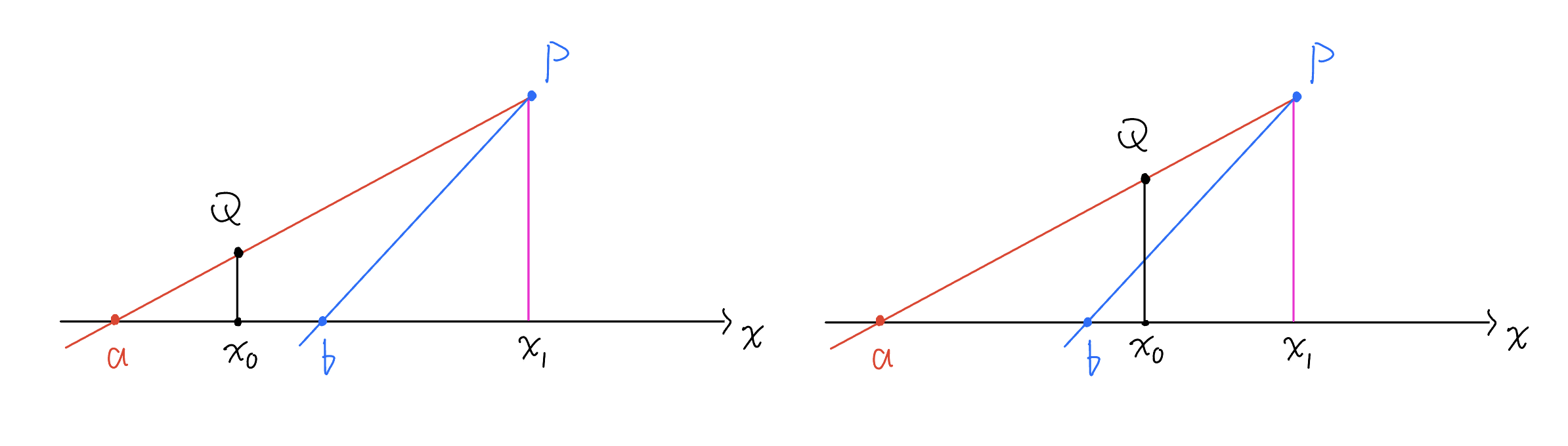

\[y_1^2\le 4\phi(x_1)\psi(x_1).\tag4\]If $x_0>a$, then $f(x_1)-f(x_0)$ is no less than the area of the trapezoid formed by $P$, $Q$, $x_0$, and $x_1$. Let $b$ be the midpoint of $a$ and $x_1$ and connect $b$ and $P$:

If $a<x_0\le b$, then $f(x_1)-f(x_0)$ is no less than the area of the triangle formed by $P$, $b$, and $x_1$, so

\[2\phi(x_1)\ge f(x_1)-f(x_0)\ge\frac12(x_1-b)y_1=\frac14(x_1-a)y_1.\]Consequently, we obtain

\[y_1^2\le 8\phi(x_1)\psi(x_1).\tag5\]If $b<x_0\le x_1$, then $y_0\ge y_1/2$, so

\[y_1\le 2y_0=2[\psi(x_1)(x_0-x_1)+2y_1],\]which indicates that $y_1\le2\psi(x_1)(x_1-x_0)$. Because we can use Lemma 1 when (3) is satisfied, we assume the negation of (3) here so that

\[y_1\le2\psi(x_1)\sqrt{4\phi(x_1)/\psi(x_1)}=4\phi^{\frac12}(x_1)\psi^{\frac12}(x_1).\tag6\]Combining Lemma 1, (4), (5), and (6), we successfully obtain the conclusion of Lemma 1 under weaker hypotheses:

Theorem 2: Let $f\in C^2[x_0,+\infty)$ with $x_0>0$ and $\phi,\psi$ be defined as in (2). Then

\[\vert f'(x)\vert\le 8\phi^{\frac12}(x)\psi^{\frac12}(x).\quad(x>2x_0)\]Generalizations

In the previous section, we showed that $f'$ can be estimated using the information of $f$ and $f''$. In this section, we generalize this principle to higher orders. That is to say, information about $f$ and $f^{(n)}$ can be used to establish estimates for $f^{(k)}$ for $0<k<n$.

Without loss of generality, assume $f\in C^n[x_0,+\infty)$ is real-valued with $x_0>0$ and define

\[\phi(x)=\sup_{x_0\le x'\le x}\vert f(x')\vert,\quad\psi(x)=\sup_{x_0\le x'\le x}\vert f^{(n)}(x')\vert.\tag7\]By examining (2), we conjecture the order of $f^{(k)}$ should not exceed $\phi^{1-\frac kn}\psi^{\frac kn}$, so we reasonably define

\[g_k(x)=\sup_{x_0\le x'\le x}{\vert f^{(k)}(x')\vert\over\phi^{1-\frac kn}(x')\psi^{\frac kn}(x')},\quad g(x)=\max_{0<k<n}g_k(x),\tag8\]Hence, it suffices to prove that $g(x)$ is bounded as $x\to+\infty$.

Since there are no ambiguity with variables, we omit the “$(x)$” in functions for brevity.

As a result of our definition of $g$, there is

\[\vert f''\vert\le\phi^{1-\frac 2n}\psi^{\frac2n}g,\quad(x>x_0)\]so by Theorem 2, there is

\[\vert f'\vert\le 8\phi^{\frac12(1+1-\frac2n)}\psi^{\frac12(\frac2n)}h^{\frac12}=8\phi^{1-\frac1n}\psi^{\frac1n}g^{\frac12}.\quad(x>2x_0)\]Plugging the above refined bound of $f'$ and the bound $\vert f'''\vert\le\phi^{1-\frac3n}\psi^{\frac3n}h$ into Theorem 2, we can refine the estimate of $f''$ by

\[\vert f''\vert\le\phi^{1-\frac2n}\psi^{\frac2n}g^{1-2^{-2}}.\quad(x>4x_0)\]Proceed inductively, we obtain for all $0<k<n$ that

\[\vert f^{(k)}\vert\le 8^{2-2^{1-k}}\phi^{1-\frac kn}\psi^{\frac kn}g^{1-2^{-k}}.\quad(x>2^{k}x_0)\]Plugging this into (8), we obtain $g_k\le 8^{2-2^{1-k}}g^{1-2^{-k}}$, so

\[g\le 8^{2-2^{2-n}}g^{1-2^{1-n}}\Rightarrow g^{2^{1-n}}\le 8^{2-2^{2-n}}.\]Simplifying everything, we deduce

Theorem 3: Let $f\in C^n[x_0,+\infty)$ with $x_0>0$ and $\phi,\psi$ be defined as in (7). Then for $0<k<n$, there is

\[\vert f^{(k)}(x)\vert\le 8^{2^n-2}\phi^{1-\frac kn}(x)\psi^{\frac kn}(x).\quad(x>2^{n-1}x_0)\]By the nature of the exponents of $\phi$ and $\psi$ in the above inequality, Theorem 3 may be regarded as a convexity result for derivatives.

If $f$ tends to a limit and $f^{(n)}$ is bounded, then we have can generalize Theorem 1 to the statement that if $f\in C^n[x_0,+\infty)$ such that $f$ tends to a limit and $f^{(n)}$ is bounded as $x\to+\infty$, then $f^{(k)}\to0$ for all $0<k<n$ as $x\to+\infty$.

The case when $x$ is near a finite number

By making constructions similar to those in the proof of Theorem 2 and Theorem 3, we can also establish convexity results when $x$ is approaching a finite number from one side.

Theorem 4: Let $f\in C^n(0,x_0]$ and

\[\phi=\sup_{x\le x'\le x_0}\vert f(x')\vert,\quad\psi=\sup_{x\le x'\le x_0}\vert f^{(n)}(x')\vert.\]Then there exists $A_n>0$ and $0<B_n<1$ such that for all $0<k<n$, we have

\[\vert f^{(k)}(x)\vert\le A_n\phi^{1-\frac kn}(x)\psi^{\frac kn}(x).\quad(0<x<B_nx_0)\]Conclusion

In this article, we began our discussion by determining a sufficient condition to ensure $f'(x)\to0$ when $f(x)$ has a limit as $x\to+\infty$. Subsequently, we move on to establishing bounds for $f'$ given information concerning $f$ and $f''$ (Theorem 2). Finally, we generalize this to convexity results relating $f$ and its higher-order derivatives (Theorem 3 and Theorem 4).

It should be noted that our theorems, proved for real-valued functions, are also valid for complex-valued functions except that the constant coefficients in the resulting bounds have to be multiplied by $\sqrt2$.

-

Hardy, G. H., & Littlewood, J. E. (1913). Contributions to the Arithmetic Theory of Series. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, s2-11(1), 411–478. ↩