Introduction to the transformations of elliptic functions

special-functions complex-analysis elliptic-functionsIn his Fundamenta Nova, Jacobi introduced his elliptic functions only to investigate the equation:

\[{\mathrm dy\over\sqrt{1-y^2}\sqrt{1-k^2y}}={\mathrm dx\over M\sqrt{1-x^2}\sqrt{1-\ell^2x^2}}.\tag1\]$k$ and $l$ are assumed to lie in $(0,1)$ throughout this article.

Particularly, he was seeking expressions of $y$ in terms of $x$ for which $M$ is some constant. In this article, we present Jacobi's imaginary transformation and Landen's transformation, which are important special cases that motivated Jacobi to study the general formula (1).

Jacobi's imaginary transformation

For the sake of convenience, let $y=\sin\alpha$ and $x=\sin\beta$, so (1) is equivalent to

\[{\mathrm d\alpha\over\sqrt{1-k^2\sin^2\alpha}}={\mathrm d\beta\over M\sqrt{1-\ell^2\sin^2\beta}}.\tag2\]Using Weierstrass substitution $s=\tan\frac\alpha2$, we obtain

\[\sin\alpha={2s\over1+s^2},\quad\mathrm d\alpha={2\over1+s^2}\mathrm ds,\]so the left-hand side of (2) becomes

\[{\mathrm d\alpha\over\sqrt{1-k^2\sin^2\alpha}}={\mathrm ds\over\sqrt{s^4+2s^2(1-2k^2)+1}}.\tag3\]Let $k'=\sqrt{1-k^2}$ and $t=is$, so we obtain

\[{\mathrm ds\over\sqrt{s^4+2s^2(1-2k^2)+1}}={\mathrm ds\over i\sqrt{t^4+2t^2(1-2k'^2)+1}}.\]Similar to how we prove (3), plugging $t=\tan\frac\beta2$ into the above formula gives

\[{\mathrm ds\over\sqrt{t^4+2t^2(1-2k'^2)+1}}={\mathrm d\beta\over\sqrt{1-k'^2\sin^2\beta}}.\]Finally, combining this with (2) and (3), we deduce

\[{\mathrm d\alpha\over\sqrt{1-k^2\sin^2\alpha}}={\mathrm d\beta\over i\sqrt{1-k'^2\sin^2\beta}}.\tag4\]In particular,

\[\sin\alpha={-2it\over1-t^2}=-i\tan\beta.\tag5\]After setting $x=\sin\beta$ in (5), we obtain a special case of (1) in which $\ell=k'$, $M=i$, and $y=-ix/\sqrt{1-x^2}$, which is known as the Jacobi's imaginary transformation. This transformation explains the origin of the notion of the complementary elliptic modulus $k'$.

Landen's transformation

Unlike Jacobian elliptic transformation, Landen's transformation is much more popular as they appear in many calculus textbooks as an exercise for students to perform change-of-variable procedures within an integral.

Indeed, playing with algebraic expressions does give us the right expressions (see Paramanand Singh's blog), but this does not reflect the beauty of Landen's transformation. Consequently, in this section, we pursue a geometric approach that makes Landen's substitution much more motivating.

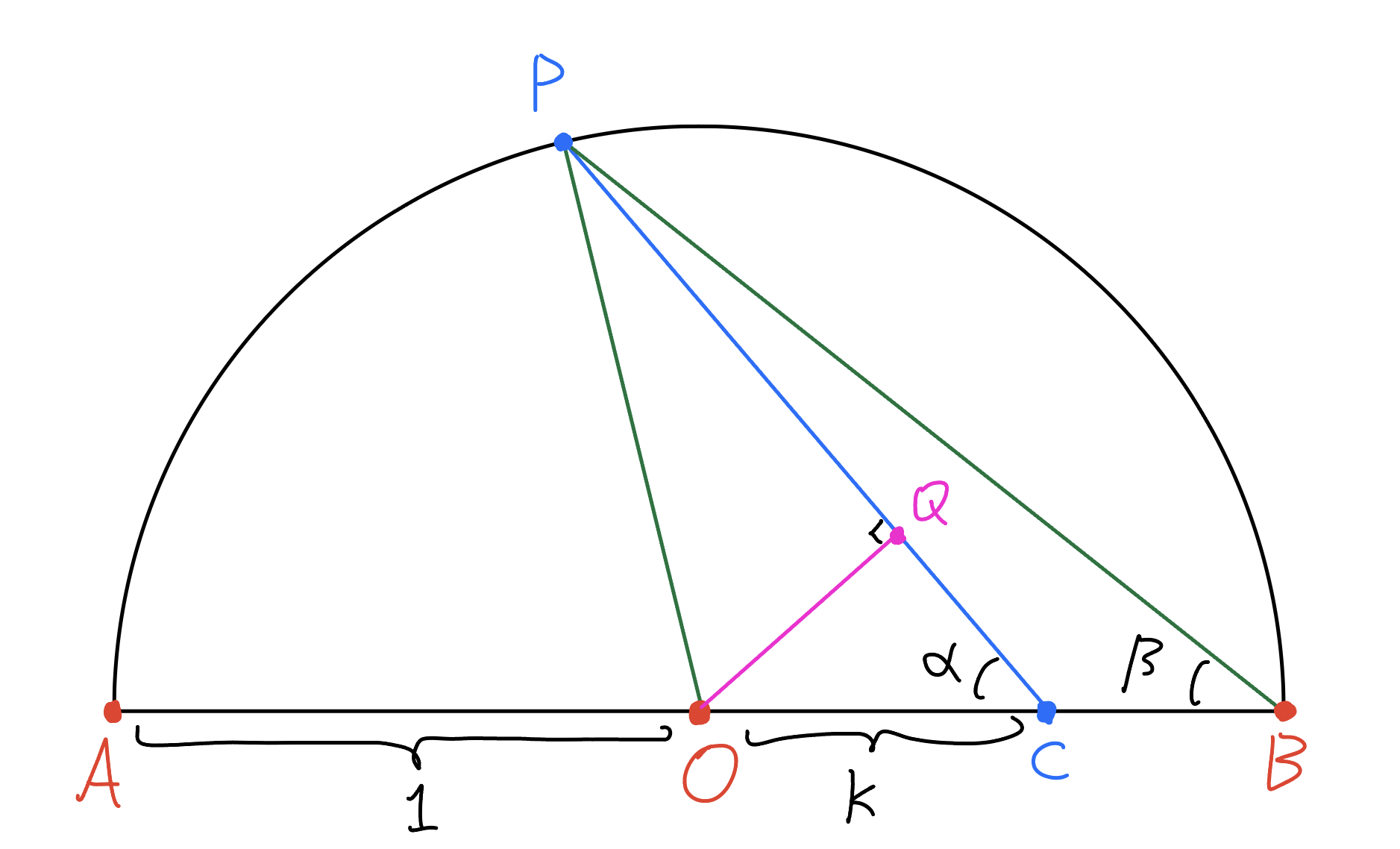

The figure is constructed via the following straightedge-and-compass instructions:

$A$ and $O$ be two points. $a$ be a circle centering $O$ with radius $\vert OA\vert$ that intersects ray $\overrightarrow{AO}$ at $B$. $P$ and $C$ be arbitrary points on $a$ and $\overline{OB}$ respectively. $Q$ be chosen on $PC$ such that $OQ\perp PC$. Finally, set $\vert OA\vert=1$, $\vert OC\vert=k$, $\angle PCA=\alpha$, and $\angle PBA=\beta$.

From the property of circle, we immediately have $\vert OP\vert=1$, $\angle POA=2\beta$, and $\angle OPC=2\beta-\alpha$, so

\[\vert OQ\vert=k\sin\alpha=\sin(2\beta-\alpha).\]Differentiating gives

\[\begin{aligned} k\cos\alpha\mathrm d\alpha &=\cos(2\beta-\alpha)(2\mathrm d\beta-\mathrm d\alpha). \\ {\mathrm d\alpha\over\cos(2\beta-\alpha)}&={2\mathrm d\beta\over k\cos\alpha+\cos(2\beta-\alpha)}. \\ {\mathrm d\alpha\over\vert PQ\vert}&={2\mathrm d\beta\over\vert CQ\vert+\vert PQ\vert}. \end{aligned}\tag6\]From the figure, it is clear that $\vert PC\vert=\vert CQ\vert+\vert PQ\vert$ and the law of cosines applied to $\triangle OPC$ gives

\[\begin{aligned} \vert PC\vert^2 &=\vert OC\vert^2+\vert OP\vert^2-2\vert OC\vert\cdot\vert OP\vert\cos(\pi-2\beta) \\ &=1+k^2+2k\cos(2\beta)=(1+k)^2-4k\sin^2\beta, \\ \end{aligned}\]so (6) is effectively transformed into

\[{\mathrm d\alpha\over\sqrt{1-k^2\sin^2\alpha}}={2\over1+k}{\mathrm d\beta\over\sqrt{1-\left(2\sqrt k\over1+k\right)^2\sin^2\beta}}.\tag7\]Because $\vert PB\vert=2\cos\beta$, applying the law of sines to $\triangle PBC$ gives us

\[\begin{aligned} \sin\alpha &=\sin(\pi-\alpha)={\vert PB\vert\over\vert PC\vert}\sin\beta \\ &={2\over1+k}{\sin\beta\cos\beta\over\sqrt{1-\left(2\sqrt k\over1+k\right)^2\sin^2\beta}}.\tag8 \end{aligned}\]Therefore, we find that (7) is a special case of (1), where $\ell=2\sqrt k/(1+k)$, $M=(1+k)/2$, and

\[y={2\over1+k}\cdot{x\sqrt{1-x^2}\over\sqrt{1-\left(2\sqrt k\over1+k\right)^2x^2}}.\]The relationship between $\ell$ and $k$ becomes more straightforward if we introduce the complementary $\ell'=\sqrt{1-\ell^2}$:

\[\ell'=\sqrt{(1+k)^2-4k\over(1+k)^2}={1-k\over1+k}.\tag9\]Transformations of Jacobian elliptic functions

The aforementioned transformations produce interesting consequences when we integrate (1) on both sides. As in the orthodox theory, let the incomplete elliptic integral be defined by

\[F(\phi,k)=\int_0^\phi{\mathrm d\theta\over\sqrt{1-k^2\sin^2\theta}}.\]For convenience, let the following denote the complete elliptic integrals:

\[K=F\left(\frac\pi2;k\right),\quad K'=F\left(\frac\pi2;k'\right),\] \[L=F\left(\frac\pi2;k\right),\quad L'=F\left(\frac\pi2;\ell'\right).\]With the notation of (2), when $u=F(\beta;\ell)$, we have $F(\alpha;k)=Mu$, and

\[y=\sin\alpha=\operatorname{sn}(u/M;k),\quad x=\sin\beta=\operatorname{sn}(u;\ell)\tag{10}\]With these notations, we can demonstrate the impact of the above transformations on Jacobian elliptic functions.

Jacobi's imaginary transformation of elliptic functions

When $\ell=k'$, it is clear that $L=K'$ and $L'=K$. As for elliptic functions, it follows from (5) and (10) that

\[\operatorname{sn}(iu;k)={\sin\beta\over i\sin\beta}={\operatorname{sn}(u;k')\over i\operatorname{cn}(u;k')}.\tag{11}\]and

\[\operatorname{cn}(iu;k)={1+s^2\over1-s^2}={1+t^2\over1-t^2}={1\over\operatorname{cn}(u;k')}.\tag{12}\]Differentiating gives

\[-i\operatorname{sn}(iu;k)\operatorname{dn}(iu;k)={-\operatorname{sn}(u;k')\operatorname{dn}(u;k')\over\operatorname{cn}^2(u;k')},\]so we obtain Jacobi's imaginary transformation of $\operatorname{dn}$ too:

\[\operatorname{dn}(iu;k)={\operatorname{dn}(u;k')\over\operatorname{cn}(u;k')}.\tag{13}\]Landen's transformation of elliptic functions

In the case of Landen's transformation, $\ell=2\sqrt k/(1+k)$. Because of (8), $\alpha\to\pi$ when $\beta\to\frac\pi2$, so

\[L={k+1\over2}F(\pi,k)=(k+1)K.\tag{14}\]Because inverting (9) gives

\[\ell'+1={2\over k+1},\quad k={1-\ell'\over1+\ell'},\]we have $k'=2\sqrt{\ell}/(1+\ell)$, so the arguments for (14) give us

\[K'=(\ell'+1)L',\quad 2L'=(k+1)K'.\tag{15}\]From (10), we also obtain Landen's transformations of elliptic functions:

\[\operatorname{sn}((1+\ell')u;k)=(1+\ell'){\operatorname{sn}(u;\ell)\operatorname{cn}(u;\ell)\over\operatorname{dn}(u;\ell)}.\tag{16}\]From identities connecting Jacobian elliptic functions, we deduce that

\[\begin{aligned} &\operatorname{dn}^2(u;\ell)-(1+\ell')^2\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell) \\ &=1-\ell^2\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)-(1+2\ell'+\ell'^2)\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell) \\ &+(1+\ell')^2\operatorname{sn^4}(u;\ell) \\ &=1-2(1+\ell')\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)+(1+\ell')^2\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell), \\ &=[1-(1+\ell')\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)]^2, \end{aligned}\]so it follows from (14) that

\[\operatorname{cn}((1+\ell')u;k)={1-(1+\ell')\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)\over\operatorname{dn}(u;\ell)}.\tag{17}\]As for $\operatorname{dn}((1+\ell')u;k)$, note that

\[\begin{aligned} &\operatorname{dn}^2(u;\ell)-k^2(1+\ell')^2\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell) \\ &=1-\ell^2\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)-(1-\ell')^2\operatorname{sn}^2(u;\ell)\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell) \\ &=\ell'^2+\ell^2\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell)-(1-2\ell'+\ell'^2)\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell) \\ &+(1-\ell')^2\operatorname{cn}^4(u;\ell) \\ &=\ell'^2-2\ell'(1-\ell')\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell)+(1-\ell')^2\operatorname{cn}^4(u;\ell) \\ &=[\ell'-(1-\ell')\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell)]^2, \end{aligned}\]so combining with (16) gives

\[\operatorname{dn}((1+\ell')u;k)={\ell'-(1-\ell')\operatorname{cn}^2(u;\ell)\over\operatorname{dn}(u;\ell)}.\tag{18}\]Transformations of Jacobian theta functions

Similar to how we reformulate the theory of Jacobian elliptic functions via theta functions, in this section, we analyze the effect of the aforementioned transformations to Jacobian theta functions.

For convenience, we define the following quantities

\[\tau={iK'\over K},\quad\tau'={iL'\over L}.\]so it follows from this article that

\[K=\frac\pi2\vartheta_3(0\vert\tau)^2,\quad L=\frac\pi2\vartheta_3(0\vert\tau')^2.\tag{19}\] \[k={\vartheta_2^2(0\vert\tau)\over\vartheta_3^2(0\vert\tau)},\quad\ell={\vartheta_2^2(0\vert\tau')\over\vartheta_3^2(0\vert\tau')}.\tag{20}\] \[k'={\vartheta_4^2(0\vert\tau)\over\vartheta_3^2(0\vert\tau)},\quad\ell'={\vartheta_4^2(0\vert\tau')\over\vartheta_3^2(0\vert\tau')}.\tag{21}\]Jacobi's imaginary transformation of theta functions

Because the imaginary transformation sets $L=K'$ and $L'=K$, we have

\[\tau'={iK\over K'}=-\frac1\tau,\]so plugging in $K'=-i\tau K$ into (19) and taking principal square root give us

\[\vartheta_3(0\vert\tau)=(-i\tau)^{-1/2}\vartheta_3(0\vert\tau').\]This is just a special case of a more general transformation formula. Let

\[\psi(u)=e^{au^2}\vartheta_3(u\vert\tau').\]Then from the quasi periodicity of theta functions, we have

\[\vartheta_3(z+\pi\vert\tau)=\vartheta_3(z\vert\tau),\quad\vartheta_3(z+\pi\tau\vert\tau)=e^{-i\pi\tau-2iz}\vartheta_3(z\vert\tau),\] \[\psi(u+\pi)=e^{2au\pi+a\pi^2}\psi(u),\] \[\psi(u+\pi\tau')=e^{2au\pi\tau'+a\pi^2\tau'^2-i\pi\tau'-2iu}\psi(u).\]To simplify, set $a=i/\pi\tau'=-i\tau/\pi$, so

\[\psi[(u\tau-\pi)/\tau]=\psi[(u\tau)/\tau],\] \[\psi[(u\tau+\pi\tau)/\tau]=e^{-i\pi\tau-2iu\tau}\psi[(u\tau)/\tau].\]Thus, $\phi(u)=\psi(u)/\vartheta_3(u\tau\vert\tau)$ is an elliptic function. Because $\vartheta_3(z\vert\tau)$ has simple zeros iff $z\equiv\frac\pi2+{\pi\tau\over2}$ modulo $m\pi+n\pi\tau$ and $\psi(u)$ has simple zeros whenever $u\equiv{\pi\over2}+{\pi\tau'\over2}\equiv{\pi\over2}+{\pi\over2\tau}$ modulo $m\pi+n\pi/\tau$, we find that $\phi$ is an elliptic function without zeros.

Therefore, Liouville's theorem indicates that $\phi(u)=\phi(0)=(-i\tau)^{-1/2}$, so we obtain the general Jacobi's imaginary transformation of $\vartheta_3(z\vert\tau)$ (setting $z=u\tau$):

\[\vartheta_3(z\vert\tau)=(-i\tau)^{-1/2}\exp\left(z^2\over i\pi\tau\right)\vartheta_3\left(\frac z\tau\left\vert-\frac1\tau\right.\right).\tag{22}\]Exercise: Give a direct proof of (22) via Poisson summation.

For more formulas about Jacobi's imaginary transformation, consult §21.51 of Whittaker & Watson's A Course of Modern Analysis.

Landen's transformation of theta functions

From (14) and (15), we have

\[{K'\over K}=2{L'\over L},\quad\tau=2\tau',\tag{23}\]so Landen's transformation has the effect of scaling the half-period ratio of elliptic functions.

For the sake of neatness, we perform a change of variable $\tau\mapsto2\tau$ and $\tau'\mapsto\tau$.

Moreover, plugging (19) and (20) into (14) gives

\[\vartheta_3^2(0\vert2\tau)+\vartheta_2^2(0\vert2\tau)=\vartheta_3^2(0\vert\tau).\tag{24}\]From (9), we obtain

\[{\vartheta_4^2(0\vert\tau)\over\vartheta_3^2(0\vert\tau)}={\vartheta_3^2(0\vert2\tau)-\vartheta_2^2(0\vert2\tau)\over\vartheta_3^2(0\vert2\tau)+\vartheta_2^2(0\vert2\tau)}.\]Combining this with (24) gives

\[\vartheta_3^2(0\vert2\tau)-\vartheta_2^2(0\vert2\tau)=\vartheta_4^2(0\vert\tau).\tag{25}\]Multiplying (24) and (25) together gives

\[\vartheta_4^2(0\vert2\tau)=\vartheta_3(0\vert\tau)\vartheta_4(0\vert\tau).\tag{26}\]Let $z=2u/\pi L=u/\vartheta_3^2(0\vert\tau)$, so it follows from (9) and (14) that

\[{(1+\ell')u\over\vartheta_3^2(0\vert2\tau)}={2u(1+k)(1+\ell')\over\pi L}=2z.\]Therefore, (16), (17), and (18) can be transformed into identities connecting $\vartheta_r(2z\vert2\tau)$ and $\vartheta_r(z\vert\tau)$. Instead of manipulating algebraic expressions, we can give direct proofs of these theta identities by appealing to Liouville's theorem. By matching the periodicity factors, we find that $\vartheta_3(z\vert\tau)\vartheta_4(z\vert\tau)/\vartheta_4(2z\vert2\tau)$ is an elliptic function without zeros, so it must be a constant. Combining this with (26) gives

\[{\vartheta_3(z\vert\tau)\vartheta_4(z\vert\tau)\over\vartheta_4(2z\vert2\tau)}={\vartheta_3(0\vert\tau)\vartheta_4(0\vert\tau)\over\vartheta_4(0\vert2\tau)}=\vartheta_4(0\vert2\tau).\tag{27}\]For more Landen transformation identities of theta functions, consult DLMF.

Conclusion

In this article, we began our discussion of the transformation theory by making subtle substitutions inside elliptic integrals. By performing Weierstrass substitution, we obtained Jacobi's imaginary transformation. Using a geometric argument, we give a motivated proof of Landen's transformation. After that, we examine the impact of these transformations on elliptic functions and theta functions.

After Landen's transformation, one is motivated to consider the general problem of determining algebraic relationship between $k$ and $\ell$ such that

\[{K'\over K}=p{L'\over L},\tag{28}\]when $p>0$ is a rational number. Permuting the values of $k$ and $\ell$ results in replacing $p$ with $p^{-1}$ in (28), and when $p=p_1p_2$, (28) can be obtained by performing two transformations together. Thus, it is sufficient to investigate (28) when $p$ is a prime. In this case, the algebraic relation between $k$ and $\ell$ is called a modular equation.

The case where $p=2$ is solved by Landen's transformation. In Fundamenta Nova, Jacobi showed that (28) is possible for all odd prime $p$ and gave explicit expressions for $y(x)$, $k(\ell)$, and $M(k,\ell)$. For a detailed account of Jacobi's transformation theory, see Paramanand Singh's series on modular equations.

As demonstrated in this article, early approaches to transformations of elliptic functions involve heavy use of elementary algebra. Instead of delving further, we will develop a much more convenient analytic theory of transformations in the future articles using Weierstrass elliptic functions, which eventually became the theory of modular forms.