Euler's pentagonal number theorem and Dedekind eta function

number-theory special-functions complex-analysisIn the 18th century, Euler applied combinatorial methods and showed that the infinite product

\[\phi(x)=\prod_{k\ge1}(1-x^k)=(1-x)(1-x^2)(1-x^3)\cdots\tag1\]has a combinatorially meaningful power series expansion when $\vert x\vert<1$. In the 19th century, Dedekind showed that if $\Im(\tau)>0$ and

\[\eta(\tau)=e^{\pi i\tau\over12}\prod_{k\ge1}(1-e^{2\pi ik\tau})=e^{\pi i\tau\over12}\phi(e^{2\pi i\tau}),\tag2\]then $\eta$ obeys the following functional equation:

\[\eta\left(-\frac1\tau\right)=(-i\tau)^{1/2}\eta(\tau).\tag3\]From their definitions, one is motivated to think whether Euler's pentagonal number theorem can be used to deduce (3). In this article, we show that this approach is possible and elementary. To begin with, we give a combinatorial proof of Euler's power series expansion of $\phi(x)$.

Euler's pentagonal number theorem

By examining the infinite product of $\phi(x)$, we see that the coefficient for $x^n$ in its power series expansion is extremely relevant to the partition of $n$. In particular, if we look at the partial product

\[\phi_N(x)=\prod_{k\le N}(1-x^k)=\sum_{n\ge0}a_{n,N}x^n\tag4\]Then we see that $a_{n,N+1}$ is increased from $a_{n,N}$ by one if there is a new partition of $n$ into an even number of unequal parts, all being $\le N+1$. On the other hand, $a_{n,N+1}$ is decreased from $a_{n,N}$ by one if there is a new partition of $n$ into an odd number of unequal parts, all of which $\le N+1$. Because $a_{n,N}$ remains the same for every $N\ge n$, we conclude as $N\to+\infty$ that

\[\phi(x)=1+\sum_{n\ge1}[p_0(n)-p_1(n)]x^n,\tag5\]where $p_v(n)$ is the number of ways to partition $n$ into $m$ unequal parts with $m\equiv v\pmod2$.

It is exhaustive for us to compare $p_0(n)$ and $p_1(n)$ by listing all possible partitions of $n$, so we consider using a graphical representation for partitions.

Partition as a graph

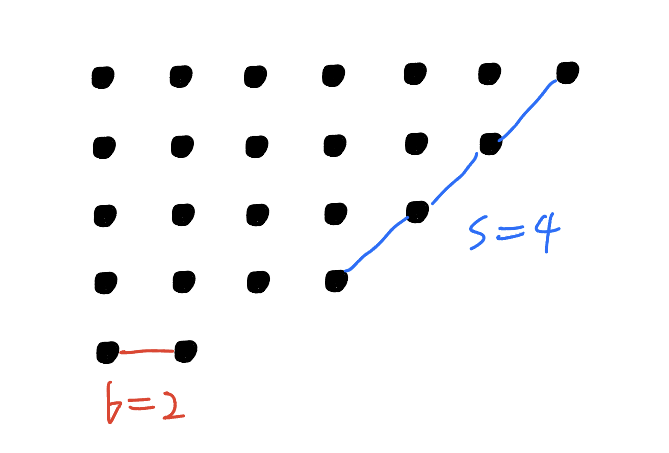

Let $n=a_1+a_2+a_3+\dots+a_m$ be a partition of $n$ into $m$ distinct elements arranged in decreasing order. Then we may construct the graph of this particular partition by drawing $a_1$ dots on the first row, $a_2$ dots on the second row, $a_i$ dots on $i$'th row and so on. For example, $24=7+6+5+4+2$ should produce the following graph:

By the construction of partition graphs, we see that when the total number $n$ of points is fixed, there is a bijection between partition graphs and partitions of $n$ into unequal parts. Hence, if we define invertible operations on the graphs, then we can create bijections between partitions of $n$.

As shown in the above picture, we let the red segment connect all the points belonging to the bottom row and the blue segment denote the longest 45-degree segment joining the right top point and other points in the graph, and $b,s$ denote the number of points connected by these segments respectively.

These segments are useful because they allow us to establish bijections between odd partitions (i.e. partitioning $n$ into an odd number of unequal parts) and even partitions when possible.

Bijection map

This argument is due to F. Franklin in 1881.

Using the line segments, we define two operations:

- Operation A: take out the red segment and rotate it by 45 degrees counterclockwise and place it to the right of the blue segment.

- Operation B: take out the blue segment and rotate it by 45 degrees clockwise and place it below the red segment.

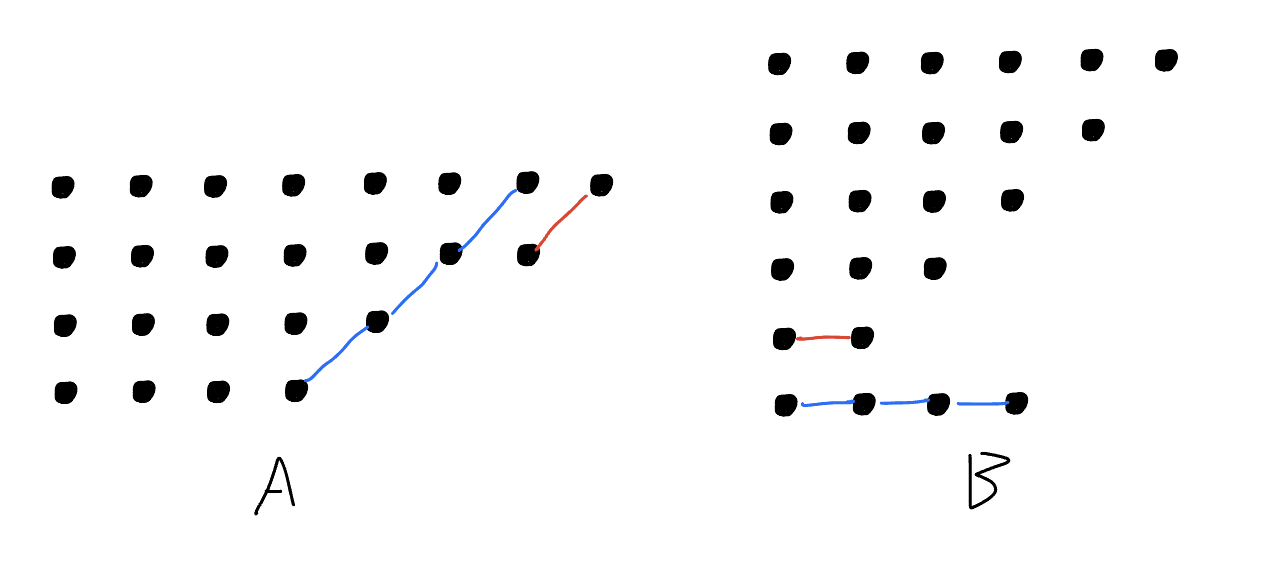

Executing these operations on the aforementioned partition graph produces the following two graphs:

We see that both operations change the number of rows in the graph by one, and when the new graph is a valid partition graph, we produce a bijection between even and odd partitions.

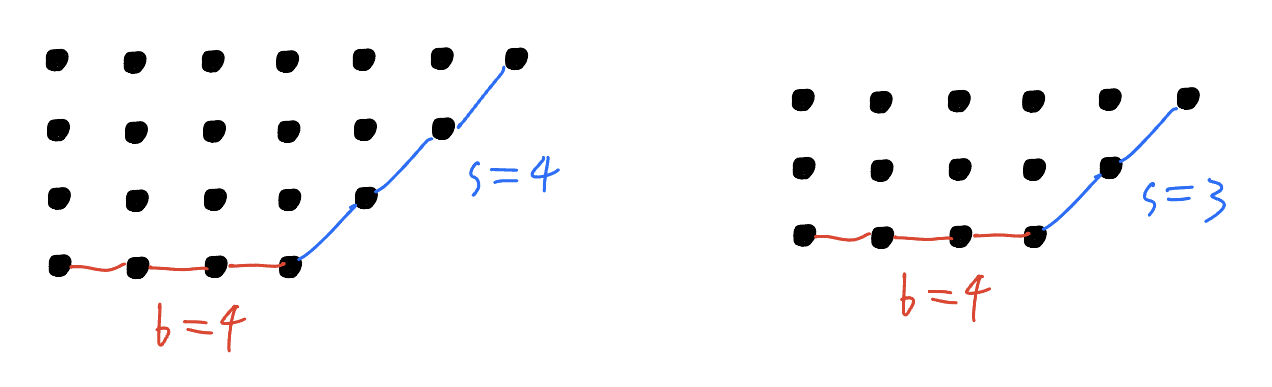

When $b<s$, the illustration indicates that A produces a partition graph, but B does not.

When $b=s$, clearly B is not admissible, and the admissibility of A needs to be considered separately according to whether the two segments are connected or not. When the segments are connected, A is not possible because the intersection point will be moved into an invalid position.

When $b>s$, it is clear that A is not admissible. When $b=s+1$ and the segments are connected, we see that B is not admissible either because it will produce a graph with two rows of the same length. However, B can be executed in all other cases.

To sum up, we see that $p_e(n)\ne p_o(n)$ if and only if $n$ belongs to the following two categories:

- $n$ can be partitioned into distinct elements such that $b=s$ and the line segments intersect. In this case, $n$ is calculated by

- $n$ can be partitioned into distinct elements such that $b=s+1$ and the line segments intersect:

When $n$ falls into the above categories, we see that there is exactly one partition that cannot be mapped using operation A or B, so we have $p_s(n)=p_{s-1}(n)+1$. In other words, when $n$ is in the form of (6) or (7), we have $p_0(n)-p_1(n)=(-1)^s$. Therefore, we obtained the following expansion:

\[\phi(x)=1+\sum_{s\ge1}(-1)^s[x^{s(3s-1)/2}+x^{s(3s+1)/2}].\tag8\]Observe that $s(3s+1)=(-s)[3(-s)-1]$, so we obtain a shorter form of (8):

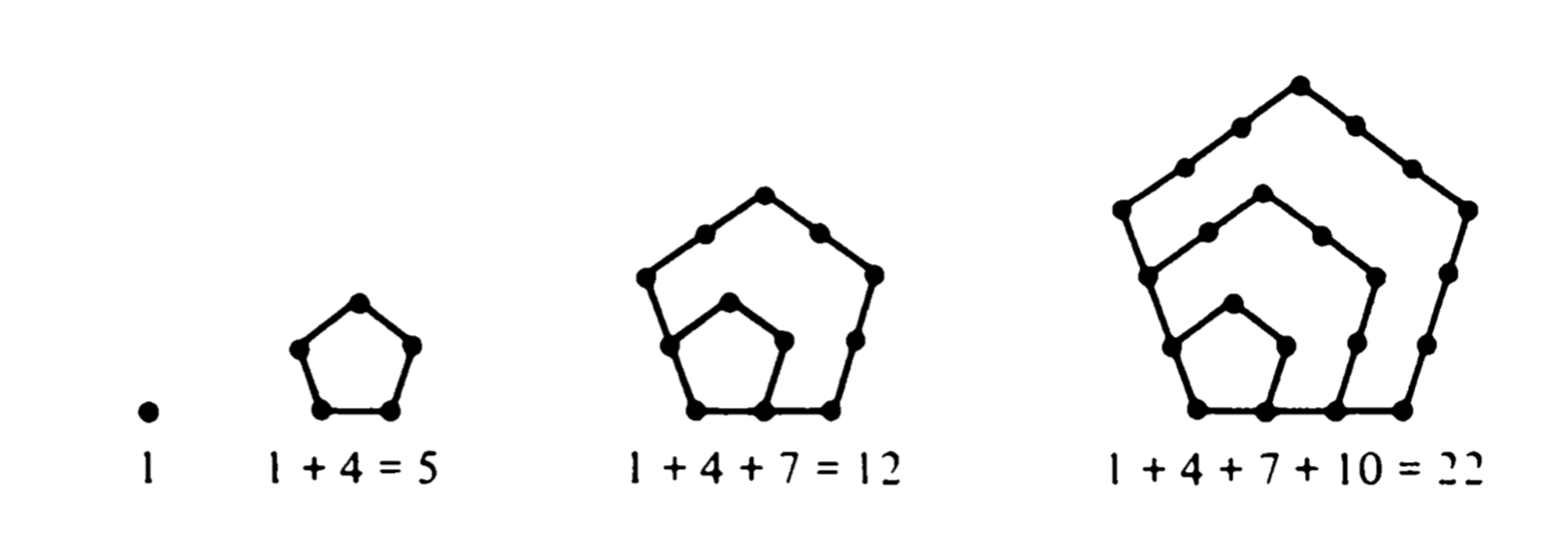

\[\phi(x)=\prod_{n\ge1}(1-x^n)=\sum_{s\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^sx^{s(3s-1)/2}.\tag9\]Formula (9) is known as the pentagonal number theorem as numbers in the form of (7) can be arranged into pentagons:

Picture taken from p. 311 of Apostol's Introduction to Analytic Number Theory.

Dedekind eta function

Let $y>0$ and $x=e^{-2\pi y}$. Then (9) becomes

\[f(y)=\phi(e^{-2\pi y})=\sum_{s\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^se^{-\pi y(3s^2-s)}.\tag{10}\]Now, let $g(t)$ be defined by

\[g(t)=e^{-\pi it-\pi y(3t^2-t)}=\exp\left\{-3\pi y\left[t^2-2\cdot\frac t6\left(1+{i\over y}\right)\right]\right\}.\tag{10}\]Then $f(y)=\sum_{s\in\mathbb Z}g(s)$. By Poisson summation formula, $f(y)=\sum_{k\in\mathbb Z}\hat g(k)$, where $\hat g$ is the Fourier transform of $g$:

\[\hat g(k)=\int_{-\infty}^\infty\exp\left\{-3\pi y\left[t^2-2\cdot\frac t6\left(1+{i\over y}\right)\right]-2\pi ikt\right\}\mathrm dt\tag{11}\]After completing the squares, we obtain

\[\hat g(k)=\exp\left\{ {\pi y\over12}\left(1+{i(2k+1)\over y}\right)^2\right\}\int_{-ia_k-\infty}^{-ia_k+\infty} e^{-3\pi yu^2}\mathrm du, \tag{12}\]where $a_k=(2k+1)/6y$. Because $e^{-z^2}$ vanishes whenever $\Im(z)$ lies in a fixed interval and $\vert\Re(z)\vert\to\infty$, we can shift the path of integration in (12) to the real axis and apply the property of the Gaussian integral to obtain

\[\begin{aligned} \hat g(k) &={1\over\sqrt{3y}}\exp\left\{ {\pi y\over12}+{\pi i(2k+1)\over6}-{\pi(2k+1)^2\over12y}\right\} \\ &={1\over\sqrt{3y}}\exp\left\{ {\pi\over12}\left(y-\frac1y\right)+{\pi ik\over3}+{\pi i\over6}-{\pi(k^2+k)\over3y}\right\}. \end{aligned}\tag{13}\]Combining everything, we deduce that

\[f(y)={1\over\sqrt{3y}}\exp\left\{ {\pi\over12}\left(y-\frac1y\right)+{\pi i\over6}\right\}\underbrace{\sum_{k\in\mathbb Z}\exp\left\{ {\pi ik\over3}-{\pi(k^2+k)\over3y}\right\}}_S.\tag{14}\]Because the $S$ converges absolutely, we can split the sum according to the congruence class of $k$ modulo 3:

\[S=\sum_{k\equiv0\pmod3}+\sum_{k\equiv1\pmod3}+\sum_{k\equiv2\pmod3}=S_0+S_1+S_2.\tag{15}\]For $S_0$, let $k=3m$ so that

\[\begin{aligned} S_0 &=\sum_{m\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^me^{-\pi(3m^2+m)/y} \\ &=\sum_{n\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^ne^{-\pi(3n^2-n)/y}=f\left(\frac1y\right).\quad(n=-m) \end{aligned}\tag{16}\]For $S_1$, under the substitution $k=3m+1$, we have

\[\begin{aligned} S_1 &=e^{\pi i/3}\sum_{m\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^me^{-\pi(3m+1)(3m+2)/3y}\\ &=e^{\pi i/3}\sum_{n\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^ne^{-\pi(3n-1)(3n-2)/3y}\quad(n=-m) \\ &=-e^{\pi i/3}\sum_{r\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^re^{-\pi(3r+2)(3r+1)/3y}.\quad(r=n+1) \end{aligned}\tag{17}\]Since the last line is exactly $-S_1$, we conclude $S_1=0$. For the remaining $S_2$, the substitution $k=3m-1$ gives

\[S_2=e^{-\pi i/3}\sum_{m\in\mathbb Z}(-1)^me^{-\pi m(3m-1)/y}=e^{-\pi i/3}f\left(\frac1y\right).\tag{18}\]Therefore, by combining (16), (17), and (18), we see that (14) becomes

\[\begin{aligned} f(y) &={e^{\pi i/6}(1-e^{-\pi i/3})\over\sqrt{3y}}\exp\left\{ {\pi\over12}\left(y-\frac1y\right)\right\}f\left(\frac1y\right) \\ &={2\over\sqrt3}\cos\left(\pi\over6\right)y^{-1/2}\exp\left\{ {\pi\over12}\left(y-\frac1y\right)\right\}f\left(\frac1y\right). \end{aligned}\tag{19}\]Notice that $\cos(\pi/6)=\sqrt3/2$, so (19) becomes the following functional equation:

\[f(y)=y^{-1/2}\exp\left\{ {\pi\over12}\left(y-\frac1y\right)\right\}f\left(\frac1y\right).\tag{20}\]Although we have only proven (20) for real positive $y$, it follows from the principle of analytic continuation that this functional equation continues to be valid when $y$ lies on the right half plane. Under the substitution $y=-i\tau$, we have $e^{-\pi y/12}f(y)=\eta(\tau)$, so (20) becomes the functional equation (3) for Dedekind eta function.

Conclusion

In this article, we began our journey by analyzing the infinite product $\phi(x)$ in (1) using combinatorial methods. After deducing the pentagonal number theorem, we set $x=e^{-2\pi y}$ and perform Poisson summation to obtain a functional equation for $\phi(x)$ and $\eta(\tau)$.

I came up with this proof yesterday and thought that this was something that has never been done before. However, after a series of Internet searching, I found that the exact same method was discovered by Ze-Yong Kong and Lee-Peng Teo on February 7 this year. This is why I wrote a blog post instead of a research paper today.