The distribution of prime divisors and Erdös-Kac theorem

number-theory complex-analysisAlthough prime numbers and statistics appear to be ideas that are seemingly remote from each other, it is still possible for us to discover some remarkable connections between them. In this article, we are going to investigate the statistical properties of the distinct prime divisor counting function $\omega(n)$.

Mean value of $\omega(n)$

Let $\mu_N$ denote the mean of first $N$ $\omega(n)$. Then by definition, we have

\[\mu_N=\frac1N\sum_{n\le N}\omega(n)=\frac1N\sum_{n\le N}\sum_{p\vert n}1.\]To continue, we interchange the order of summation so that $p$ is summed first and $n$ is summed later:

\[\mu_N=\frac1N\sum_{p\le N}\sum_{\substack{n\le N\\p\vert n}}1=\frac1N\sum_{p\le N}\left\lfloor\frac Np\right\rfloor.\]Because $\lfloor t\rfloor=t+O(1)$ and

\[\sum_{p\le x}\frac1p=\log\log x+B_1+O\left(1\over\log x\right)\tag1,\]we obtain

\[\mu_N=\log\log N+B_1+O\left(1\over\log N\right)\sim\log\log N.\tag2\]Therefore, we see the mean of $\omega(n)$ in $1\le n\le N$ is well approximated by $\log\log N$ as $N$ grows large.

Variance and standard deviation of $\omega(n)$

From (2), we see that the variance of $\omega(n)$ is given by the difference between the second moment and square mean:

\[\sigma_N^2=\frac1N\sum_{n\le N}\omega(n)^2-\mu_N^2.\]To evaluate the second moment, interchanging the order of summation gives

\[\sum_{n\le N}\omega(n)^2=\sum_{p_1,p_2\le N}\sum_{\substack{n\le N\\ [p_1,p_2]\vert n}}1=\sum_{\substack{p_1p_2\le N\\p_1\ne p_2}}\left\lfloor N\over p_1p_2\right\rfloor+\sum_{p\le N}\left\lfloor\frac Np\right\rfloor.\tag3\]For the first sum, note that

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{\substack{p_1p_2\le N\\p_1\ne p_2}}\left\lfloor N\over p_1p_2\right\rfloor &=\sum_{\substack{p_1p_2\le N\\p_1\ne p_2}}{N\over p_1p_2}+O(N) \\ &=\sum_{p_1p_2\le N}{N\over p_1p_2}+O(N)+O\left(\sum_p{N\over p^2}\right), \end{aligned}\]so we are left with the partial sum of $1/p_1p_2$ over $p_1p_2\le N$. If we upper-bound this sum using the region $p_1,p_2\le N$ and lower-bound this sum by $p_1,p_2\le\sqrt N$, then we end up with

\[\sum_{p_1p_2\le N}{1\over p_1p_2}=(\log\log N)^2+O(\log\log N),\]but combining this estimate with (3) only gives $\sigma_N^2=O(\log\log N)$. We are definitely not satisfied with this bound because we cannot rule out the possibility that $\sigma_N^2=o(\log\log N)$.

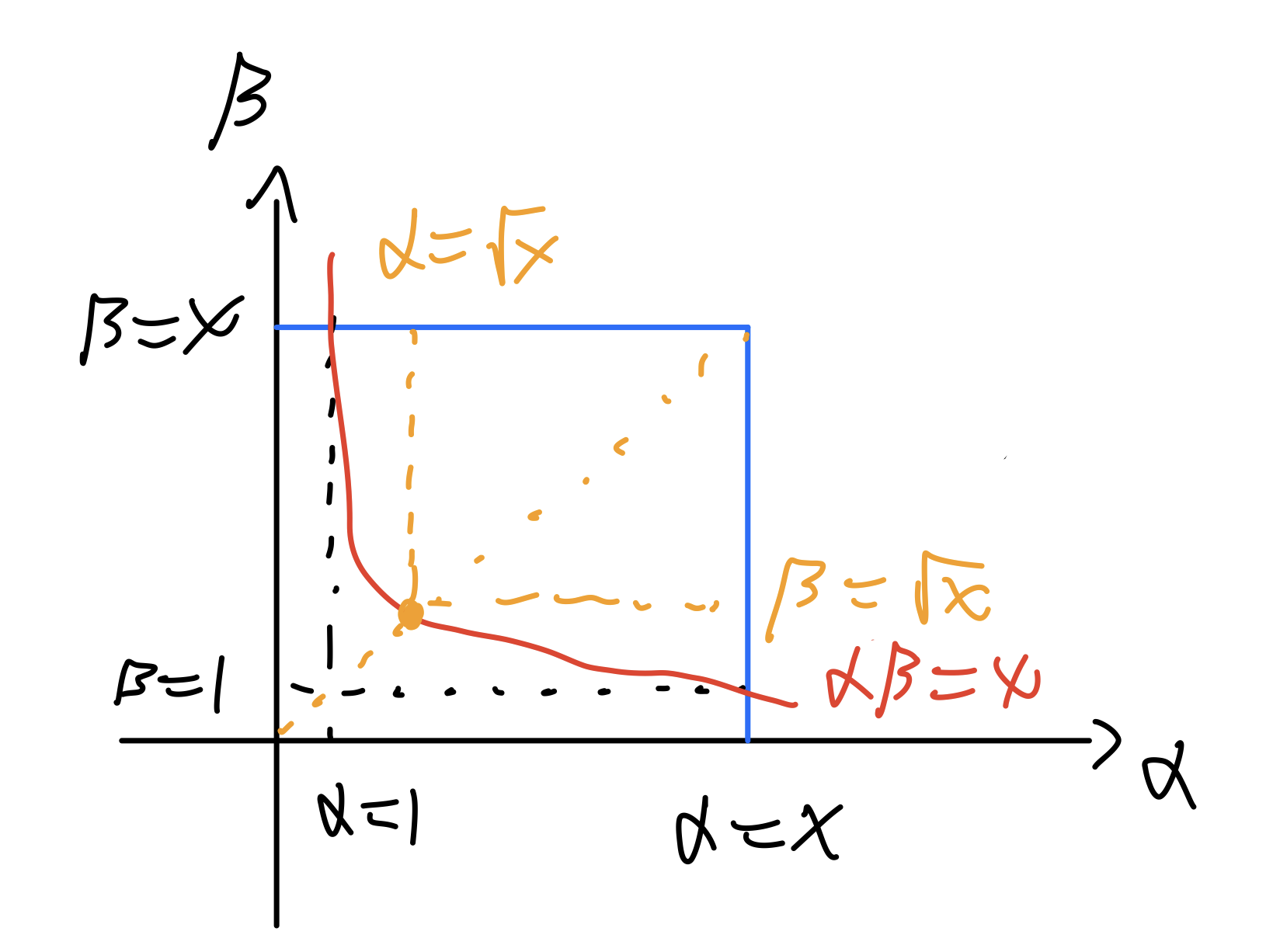

To treat this double sum with care, we first plot the hyperbola $\alpha\beta=x$:

We observe that to sum over the region $\alpha\beta\le x$. It suffices to first sum over $\alpha,\beta\le x$ and subtract the sums over $\{(\alpha,\beta):\sqrt x<\alpha,\beta\le x\}$, $\{(\alpha,\beta):\beta\le\sqrt x,x/\beta<\alpha\le x\}$, and $\{(\alpha,\beta):\alpha\le\sqrt x,x/\alpha<\beta\le x\}$. Therefore, we have

\[\sum_{p_1p_2\le N}{1\over p_1p_2}=\left(\sum_{p\le N}\frac1p\right)^2-2\sum_{p_1\le\sqrt N}{1\over p_1}\sum_{N/p_1<p\le N}{1\over p_2}-\left(\sum_{\sqrt N<p\le N}\frac1p\right)^2.\]From (1), we see that

\[\sum_{\sqrt N<p\le N}\frac1p=\log2+O\left(1\over\log N\right)=O(1)\]and for $p_1\le\sqrt N$ that

\[\sum_{N/p_1<p_2\le N}{1\over p_2}\ll\log\left(1-{\log p\over\log N}\right)^{-1}\ll{\log p\over\log N},\]so we have

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{p_1p_2\le N}{1\over p_1p_2} &=\left(\sum_{p\le N}\frac1p\right)^2+O(1) \\ &=(\log\log N)^2+2B_1\log\log N+O(1). \end{aligned}\]Plugging this back into (3) and combining the result with (2) gives us

\[\sigma_N^2=\log\log N+O(1)\sim\log\log N.\]Therefore, we conclude that the standard deviation of $\omega(n)$ in $1\le n\le N$ is well approximated by $\sqrt{\log\log N}$ when $N$ grows large.

Up to now, we have studied the mean and standard deviation in the distribution of prime divisors, and this information is sufficient to tell about the specific distribution pattern of the values of $\omega(n)$.

Limiting distribution of $\omega(n)$

Many problems that are difficult to handle become straightforward when we study them in the frequency domain. In probability theory, characteristic functions are the exact tools we need.

For some random variable $X$, its characteristic function is given by the mean of $e^{itX}$. In the case we are studying, the characteristic function $\varphi_N(t)$ of the Z score of $\omega(n)$ is given by

\[\varphi_N(t)=\frac1N\sum_{n\le N}e^{it(\omega(n)-L^2)/L},\quad L=\sqrt{\log\log N}.\tag4\]Because we are investigating the distribution of $\omega(n)$ when $N$ is large, we hope to work with an asymptotic estimate of $\varphi_N(t)$ instead of the exact formula in (4). Hence, in this section, we will derive an asymptotic formula for

\[S(x,y)=\sum_{n\le x}e^{iy\omega(n)}\quad(x\to+\infty,y\to0).\]Since $S(x,y)=x$, we assume $y\ne0$ in the derivation process.

Asymptotic formula for $S(x,y)$

Since $\omega(n)$ is additive, $e^{iy\omega(n)}$ is multiplicative. As a result, $S(x,y)$ can be approached by the means of Dirichlet series. Let $F(s)=F(s;y)$ be the Dirichlet series of $e^{iy\omega(n)}$. Then Euler product expansion allows us to obtain

\[F(s)=\prod_p\left(1+\sum_{r\ge1}{e^{iy}\over p^{rs}}\right)=[\zeta(s)]^{e^{iy}}\underbrace{\prod_p\left(1+{e^{iy}\over p^s-1}\right)\left(1-{1\over p^s}\right)^{e^{iy}}}_{G(s;y)}.\tag5\]Using the power series expansion for $\log(1+z)$ allows us to conclude that $G(s;y)$ converges absolutely in $\Re(s)>1/2$ and is uniformly continuous with respect to $y$. Combining this fact with certain standard estimates for $\log\zeta(s)$ in $\zeta$'s zero-free region, one sees that there exists some $c_0,c_1>0$ such that

\[S(x,y)={x\over2\pi i}\int_\Gamma{F(s+1)\over s+1}x^s\mathrm ds+O(xe^{-c_1\sqrt{\log x}}),\tag6\]where $\Gamma$ denotes a path starting from $-c_0/\sqrt{\log x}$, rotates counterclockwise at the origin from the lower half plane, and goes back to $-c_0/\sqrt{\log x}$ from the upper-half plane. For convenience, let $H(s)$ be defined by

\[H(s)=s^{e^{iy}}F(s+1)={[s\zeta(s+1)]^{e^{iy}}G(s)\over s+1}.\]Then it follows from (5) that $H(s)$ is analytic in $\vert s\vert <1$. To continue from (6), let $u=s\log x$ so that

\[S(x,y)={x(\log x)^{e^{it}-1}\over2\pi i}\int_{\gamma}u^{-e^{iy}}H\left(u\over\log x\right)e^u\mathrm du+O(xe^{-c_1\sqrt{\log x}}),\]where $\gamma$ denotes a path starting from $-c_0\sqrt{\log x}$, rotates counterclockwise at the origin from the lower half plane, and goes back to $-c_0\sqrt{\log x}$ from the upper-half plane. Because $\cos y<1$ when $y\ne0$ approaches zero, $\gamma$ can be deformed into two line segments. This allows us to transform $S(x,y)$ into

\[S(x,y)=x(\log x)^{e^{it}-1}{\sin(\pi e^{iy})\over\pi}\int_0^{c_0\sqrt{\log x}}u^{-e^{iy}}H\left(u\over\log x\right)e^{-u}\mathrm du+O(xe^{-c_1\sqrt{\log x}}).\]By the analyticity of $H(s)$ near $s=0$ and (5), we see that as $s\to0$

\[H(s)=H(0)+O(\vert s\vert )=G(0;y)+O(\vert s\vert ).\]This indicates that when $x\to\infty$, there is

\[\int_0^{c_0\sqrt{\log x}}u^{-e^{iy}}H\left(u\over\log x\right)e^{-u}\mathrm du=G(0;y)\Gamma(1-e^{iy})+O\left(1\over\log x\right).\]Now, plugging in Euler's reflection formula for $\Gamma$ function gives

\[S(x,y)={G(0;y)\over\Gamma(e^{iy})}x(\log x)^{e^{iy}-1}\left\{1+O\left(1\over\log x\right)\right\}\]Because $G(0;y)$ is continuous, $G(0;0)=1$, and $1/\Gamma$ is entire, we see that when $y\to0$, the above expression becomes

\[S(x,y)=x(\log x)^{iy-{y^2\over 2}}\left\{1+O\left(\vert y\vert +\vert y\vert ^3+{1\over\log x}\right)\right\}.\tag7\]With (7), we will be able to calculate the pointwise limit of $\varphi_N(t)$ when $N\to+\infty$.

Erdös-Kac theorem

Plugging (7) into (4), we see that for any fixed $t$ there is

\[\begin{aligned} \varphi_N(t) &={e^{-it L}\over N}S(N,t/L)=e^{-itL}(\log N)^{i(t/L))-{(t/L)^2\over2}}\{1+O(L^{-1})\} \\ &=e^{-t^2/2}\left\{1+O\left(1\over\sqrt{\log\log N}\right)\right\}\underset{N\to+\infty}{\xrightarrow{\text{pointwise}}}e^{-t^2/2}. \end{aligned}\]Because $e^{-t^2/2}$ is exactly the characteristic function of the standard normal distribution, we see that the continuity theorem allows us to conclude that the Z score of $\omega(n)$ possesses a limiting distribution, which turns out to be the standard normal distribution. This result is known as the Erdös-Kac theorem:

Let $\beta>\alpha$ and $A(N;\alpha,\beta)$ denote the number of integers $1\le n\le N$ such that $(\omega(n)-\log\log N)/\sqrt{\log\log N}\in(\alpha,\beta]$. Then we have

\[\lim_{N\to\infty}{A(N;\alpha,\beta)\over N}={1\over\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_\alpha^\beta e^{-x^2/2}\mathrm dx.\tag8\]Originally, the theorem is proven by Erdös and Kac in 1940 using a variant of the central limit theorem. The characteristic function approach presented in this article is due to Rényi and Turán's work in 1958.

Conclusion

In this article, we began our study by investigating the average of $\omega(n)$ in $1\le n\le N$. Then, by manipulating hyperbolas, we deduce an asymptotic formula for the standard deviation of $\omega(n)$. Finally, we prove that the distribution of $\omega(n)$'s values are approximately normal when $N$ is large using its characteristic function and continuity theorem.