Analytic Proof of the Prime Number Theorem

In the previous article, we have shown that the prime number theorem is equivalent to the statement that

\[\psi(x)=\sum_{n\le x}\Lambda(n)\sim x\]In this article, we are going to present the proof of this asymptotic relation with explicit remainder.

Dirichet series and asymptotics

One way to study the asymptotic property of functions is by Dirichlet series. Let $a_n$ be nonnegative sequence and $A(x)$ be defined as follows:

\[A(x)=\sum_{n\le x}a_n\]then the associated Dirichlet series can be written as

\[F(s)=\sum_{n=1}^\infty{a_n\over n^s}=\int_{1^-}^\infty x^{-s}\mathrm dA(x)\]By a change of variable and integration by parts, we obtain the following Laplace transform relationship:

\[F(s)=\int_{0^-}^\infty e^{-st}\mathrm dA(e^t)=s\int_0^\infty e^{-st}A(e^t)\mathrm dt\]which holds whenever $s$ lies within $F(s)$'s region of convergence. Hence, we can use inverse Laplace transform to get

\[\frac12[A(x+0)+A(x-0)]=\lim_{T\to\infty}{1\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}{x^s\over s}F(s)\mathrm ds\tag1\]where $\sigma$ is chosen such that $F(s)$ conveges on $\Re(s)=\sigma$, and (1) is known as the Perron formula. To use this tool, we first need to extract properties from the Dirichlet series of $\Lambda(n)$.

Dirichlet series of $\Lambda(n)$

By the relationship between product of Dirichlet series and Dirichlet convolution, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{n=1}^\infty{\Lambda(n)\over n^s} &=\sum_{n=1}^\infty{(\mu*\log)(n)\over n^s}=\sum_{m=1}^\infty{\mu(m)\over m^s}\sum_{k=1}^\infty{\log k\over k^s} \\ &={1\over\zeta(s)}\sum_{k=1}^\infty{\log k\over k^s}=-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s) \end{aligned}\]Integral representation of $\psi(x)$

Applying Perron formula with $\sigma>1$, we have

\[\frac12[\psi(x+0)+\psi(x-0)]=\lim_{T\to\infty}{1\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds\]Without loss of generality, we can set $x$ to be half odd integer, so that it avoids the discontinuities.

\[\psi(x)=\lim_{T\to\infty}{1\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds\tag2\]Integral representation with remainder

Apparently, (2) is a qualitative expression for $\psi(x)$, but in order to obtain an asymptotic formula with remainder, we need a finite integral instead of improper integral to express $\psi(x)$. To begin with, we interchange the summation to get

\[\psi(x)=\lim_{T\to\infty}\sum_{n=1}^\infty{\Lambda(n)\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}\left(\frac xn\right)^s{\mathrm ds\over s}\tag3\]As a result, all we need is to estimate

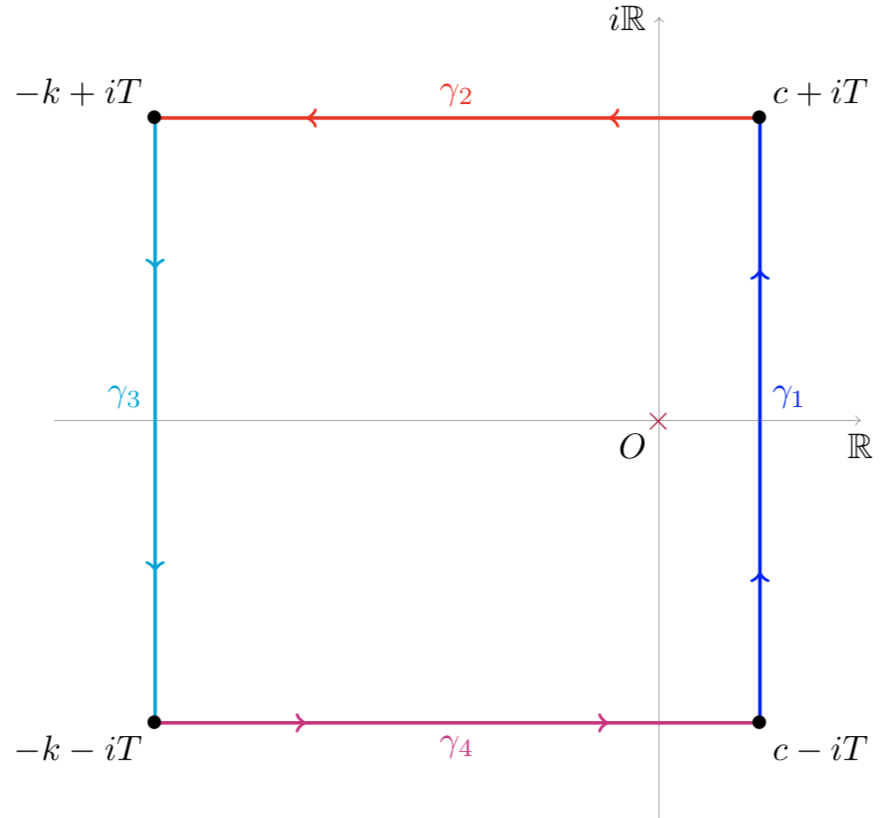

\[h_T(y)={1\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}{y^s\over s}\mathrm ds\]For $y>1$, we consider the following path of integration:

Due to the symmetry of $\gamma_2$ and $\gamma_4$, we only need to estimate one of them

\[\left\vert \int_{\gamma_4}{y^s\over s}\mathrm ds\right\vert \le\frac1T\int_{-k}^cy^r\mathrm dr\le{y^c\over T\log y}\]Moreover, due to residue theorem

\[{1\over2\pi i}\oint_{\gamma_1+\gamma_2+\gamma_3+\gamma_4}{y^s\over s}\mathrm ds=1\]and the fact that

\[\lim_{k\to\infty}\int_{\gamma_3}{y^s\over s}\mathrm ds=0\]we see that for $y>1$

\[\vert h_\infty(y)-h_T(y)\vert \ll{y^\sigma\over T\vert \log y\vert }\tag4\]By choosing a rectangle on the right half plane, it can be easily deduced that (4) holds for $0<y<1$. Due the settings that $x$ is a half odd integer, the situation where $y=1$ will not be considered. Plugging this into (3), we obtain

\[\psi(x)={1\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds +\mathcal O\left({x^\sigma\over T}\sum_{n=1}^\infty{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma\vert \log(x/n)\vert }\right)\tag5\]Since $\zeta'/\zeta$ converges absolutely when $\sigma>1$, (5) conforms to (1) as $T\to+\infty$.

Refinement of remainder

In the last section, a finite, quantitative form of $\psi(x)$'s expression is obtained, but the logarithm in the remainder is not convenient to work with when $x$ is close to $n$. Consequently, we divide the interval of sum into $n<x/2$, $x/2\le n\le2x$, and $n>2x$, so that

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{\substack{n<x/2\\ n>2x}}{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma\vert \log x/n\vert } &\le{1\over\log2}\sum_{\substack{n<x/2\\ n>2x}}{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma} \\ &\ll\sum_{n=1}^\infty{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma}=-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(\sigma) \end{aligned}\]As demonstrated before, the Dirichlet series of $\zeta(s)$ converges everywhere on $\Re(s)\ge1$ except for a simple pole at $s=1$. This means if we were to define $g(s)=(s-1)\zeta(s)$ then

\[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)={1\over s-1}-{g'\over g}(s)\]since $g(s)$ is analytic and nonzero at $s=1$, we conclude that

\[\sum_{\substack{n<x/2\\ n>2x}}{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma\vert \log(x/n)\vert }\ll{1\over\sigma-1}\tag6\]Because $\Lambda(n)\le\log n$, we rewrite the sum on $x/2\le n\le2x$ into

\[\sum_{x/2\le n\le2x}{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma\vert \log(x/n)\vert }\ll{\log x\over x^\sigma}\sum_{x/2\le n\le x}{1\over\vert \log(x/n)\vert }\tag7\]By the fact that $x$ is chosen to be half odd integer, we further partition the right-most sum into

\[\sum_{x/2\le n\le x}{1\over\vert \log(x/n)\vert }=\sum_{x/2\le n\le x-1/2}{1\over\log(x/n)}+\sum_{x+1/2\le n\le2x}{1\over\log(n/x)}\]As $a\to0$, we have $\log(1+a)\sim a$, so the partial sums become

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{x/2\le n\le x-1/2}{1\over\log(x/n)} &\ll\sum_{x/2\le n\le x-1/2}{n\over x-n}\ll x+\sum_{x/2\le n\le x-1/2}{x\over x-n} \\ &\ll x+x\int_{x/2}^{x-1/2}{\mathrm dr\over x-r}\ll x\log x \end{aligned}\] \[\begin{aligned} \sum_{x+1/2\le n\le2x}{1\over\log(n/x)} &\ll\sum_{x+1/2\le n\le2x}{x\over n-x}\ll x\int_{x+1/2}^{2x}{\mathrm dr\over r-x} \\ &=x\log{2x-x\over x+1/2-x}\ll x\log x \end{aligned}\]Plugging these back into (7), we have

\[\sum_{x/2\le n\le2x}{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma\vert \log(x/n)\vert }\ll{\log^2x\over x^{\sigma-1}}\]Finally, plugging everything into (6) and (7) into (5), we get

\[\psi(x)={1\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds +\mathcal O\left(x^\sigma\over T(\sigma-1)\right)+\mathcal O\left(x\log^2x\over T\right)\]Now, setting $\sigma=1+1/\log x$, we obtain an effective integral expression for $\psi(x)$ at half-odd integers:

\[\psi(x)={1\over2\pi i}\int_{\sigma-iT}^{\sigma+iT}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds+\mathcal O\left(x\log^2x\over T\right)\tag9\]With all these efforts, we finally transform the prime number theorem from a number-theoretic problem to a complex-analytic problem. To take down the integral, we need to extract analytic properties from the Riemann zeta function.

Zero-free region of Riemann zeta function

Since the integrand of (9) has a pole at $s=1$ with residue $x$, we wish to construct a rectangular contour that enters and leaves the critical strip so that we can prove $\psi(x)\sim x$. To avoid coping with poles due to the zero of $\zeta(s)$, we need to determine a zero-free region for $\zeta(s)$.

Nonvanishing of Riemann's zeta on $\sigma=1$

This proof was first given by La Vallée Pousin in 1896, in which he considered the quantity

\[H(\sigma)=\zeta^3(\sigma)\zeta^4(\sigma+it)\zeta(\sigma+2it)\]If $\zeta(s)$ had a zero of order $k\ge1$ at $s=1+it$, then

\[\lim_{\sigma\to1^+}H(\sigma)=0\tag{10}\]Due to the Euler product representation of $\zeta(s)$, we have

\[\log\zeta(s)=\sum_p\log{1\over1-p^{-s}}=\sum_{p^m}{\log p\over p^{ms}}=\sum_{n=2}^\infty{\Lambda(n)\over n^s\log n}\]This implies that

\[\log\vert H(\sigma)\vert =\sum_{n=2}^\infty{\Lambda(n)\over n^\sigma\log n}[3+4\cos(t\log n)+\cos(2t\log n)]\tag{11}\]Now using the double-angle formula for cosine, we have

\[3+4\cos\theta+\cos2\theta=2(\cos\theta+1)^2\ge0\]This implies we have $\vert H(\sigma)\vert \ge1$ for all $\sigma>1$, contradicting (10). Consequently, Riemann zeta function is nonzero on the line $\sigma=1$. In the next section, we will show that (11) allows us to extend the zero-free region even further. Before this, we need to find upper bounds for $\zeta(s)$.

Upper bounds for $\zeta(1+it)$

To begin with, we consider the Dirichlet series representation of $\zeta(s)$:

\[\begin{aligned} \zeta(s) &=\sum_{n=1}^N{1\over n^s}+\sum_{n=N+1}^\infty{1\over n^s} \\ &=\sum_{n=1}^N{1\over n^s}+\int_N^\infty{\mathrm dx\over x^s}-\int_N^\infty{\mathrm d\{x\}\over x^s} \\ &=\sum_{n=1}^N{1\over n^s}+\left[{x^{1-s}\over1-s}-{\{x\}\over x^s}\right]_N^\infty-s\int_N^\infty{\{x\}\over x^{s+1}}\mathrm dx \end{aligned}\]Eventually, we obtain

\[\zeta(s)=\sum_{n=1}^N{1\over n^s}+{N^{1-s}\over s-1}-s\int_N^\infty{\{x\}\over x^{s+1}}\mathrm dx\tag{12}\]Let $A>0$ be some constant, so when $\sigma\ge1-A/\log\vert t\vert $, (12) becomes

\[\vert \zeta(s)\vert \ll\sum_{n=1}^N\frac1n+\frac1t+{\vert s\vert \over N}\]When $\vert t\vert \ge e$ and $N=\lfloor\vert t\vert \rfloor$, we have

\[\zeta(1+it)\ll\log\vert t\vert\]Similarly, by taking derivative on (12) we can deduce a more general property:

\[\zeta^{(k)}(1+it)\ll\log^{k+1}\vert t\vert \tag{13}\]With these upper bounds ready, we can deduce lower bounds for $\zeta(s)$.

Lower bounds for $\zeta(1+it)$

Given (11), we have $\vert H(\alpha)\vert \ge1$, so for all $\alpha>1$ and $\vert t\vert \ge e$ there exists positive constant $K_1$ such that

\[\vert \zeta(\alpha+it)\vert \ge{1\over\vert \zeta^{3/4}(\alpha)\zeta^{1/4}(\alpha+2it)\vert }\ge{K_1(\alpha-1)^{3/4}\over\log^{1/4}\vert t\vert }\]This implies

\[\begin{aligned} \vert \zeta(1+it)\vert &=\vert \zeta(\alpha+it)-[\zeta(\alpha+it)-\zeta(1+it)]\vert \\ &\ge\left\vert \vert \zeta(\alpha+it)\vert -\vert \zeta(\alpha+it)-\zeta(1+it)\vert \right\vert \end{aligned}\]Provided that $\alpha$ can be any value greater than one, we pick $\alpha$ such that the lower bound of $\vert \zeta(\alpha+it)\vert $ is exactly twice the upper bound of the second term. That is, if we set $K_2>0$ such that $\vert \zeta(s)\vert \le K_2\log^2\vert t\vert $ on $\sigma\ge1-A/\log\vert t\vert $, then

\[\vert \zeta(\alpha+it)-\zeta(1+it)\vert \le\int_1^\alpha\vert \zeta'(r+it)\vert \mathrm dr\le K_2(\alpha-1)\log^2\vert t\vert\]then we require

\[{K_1(\alpha-1)^{3/4}\over\log^{1/4}\vert t\vert }=2K_2(\alpha-1)\log^2\vert t\vert\]Solving this equation, we get

\[\alpha-1={(K_1/2K_2)^4\over\log^9\vert t\vert }\]which implies that there exists $K_3>0$ such that

\[\vert \zeta(1+it)\vert \ge K_3\log^{-7}\vert t\vert\]An extension of zero-free region

In the previous sections, we have extracted some basic properties of $\zeta(s)$ on $\sigma=1$, and in fact these properties remain still valid when $s$ lies within a certain subset of $\sigma<1$.

\[\begin{aligned} \vert \zeta(\sigma+it)\vert &\ge\vert \vert \zeta(1+it)\vert -\vert \zeta(1+it)-\zeta(\sigma+it)\vert \vert \\ &\ge K_3\log^{-7}\vert t\vert -\int_\sigma^1\vert \zeta'(r+it)\vert \mathrm dr \\ &\ge K_3\log^{-7}\vert t\vert -K_2(1-\sigma)\log^2\vert t\vert \end{aligned}\]In order for $\zeta(s)\gg\log^{-7}\vert t\vert $ to hold, the second term must be less than some multiple of $\log^{-7}\vert t\vert $. As a result, there exists a constant $c_0$ such that whenever $1-\sigma\le c_0/\log^9\vert t\vert $ the same lower bound holds. This indicates that we can expand the zero-free region of Riemann zeta function from $\sigma\ge1$ to

\[\sigma\ge1-{c_0\over\log^9\vert t\vert }\tag{14}\]Bound for $\zeta'/\zeta$

Due to (13), we see that when $s$ lies in the region specified in (14), the logarithmic derivative of $\zeta(s)$ satisfies

\[{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\ll\log^9\vert t\vert \tag{15}\]Finally, we will show that (14) and (15) lead to the prime number theorem.

Proof of the prime number theorem

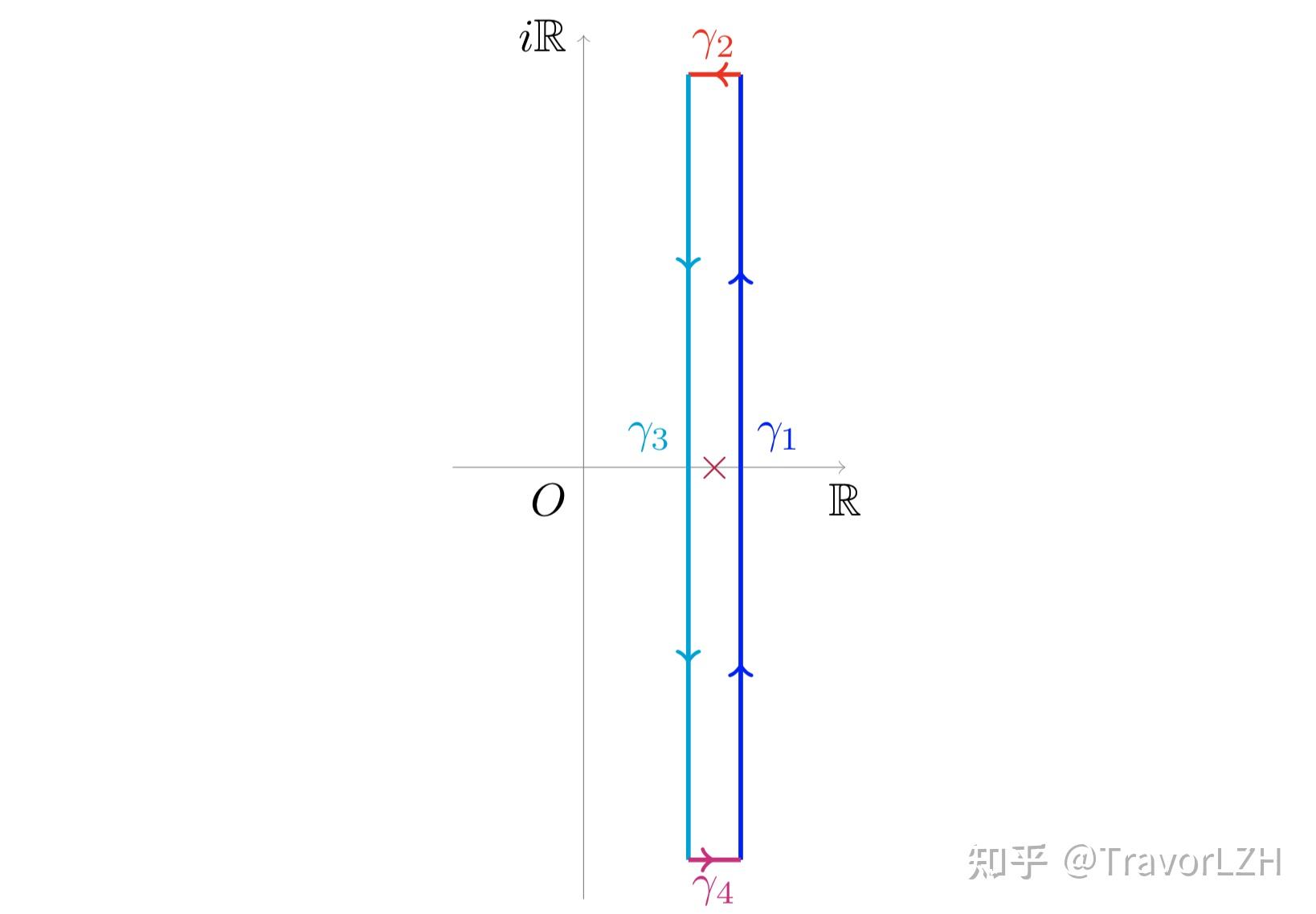

As mentioned before, we construct the following rectangle $C_T=\gamma_1+\gamma_2+\gamma_3+\gamma_4$ with end points $\delta\pm iT$ and $\sigma\pm iT$:

We set $\delta=1-c_0/\log^9T$ so that $C_T$ lies within the zero-free region of $\zeta(s)$, which implies $C_T$ only encloses the pole of the integrand at $s=1$:

\[{1\over2\pi i}\oint_{C_T}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds=x\]On $\gamma_2$ and $\gamma_4$, it is evident that $\vert s\vert \ge T$, so combined with (15) we have

\[\int_{\gamma_2+\gamma_4}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds\ll{x^\sigma\log^9T\over T}\ll{x\log^9T\over T}\]On $\gamma_3$, $\vert s\vert \ge\delta$ so

\[\int_{\gamma_3}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds\ll x^\delta\log^{10}T\]Combining everything, we have

\[{1\over2\pi i}\int_{\gamma_1}{x^s\over s}\left[-{\zeta'\over\zeta}(s)\right]\mathrm ds=x+\mathcal O\left(x^\delta\log^{10}T\right)+\mathcal O\left({x\log^9T\over T}\right)\tag{16}\]Because $\gamma_1$ represents the line going from $\sigma-iT$ to $\sigma+iT$, we can plug (16) into (9) to obtain

\[\psi(x)=x+\mathcal O\left(x^\delta\log^{10}T\right)+\mathcal O\left({x\log^9T\over T}\right)+\mathcal O\left(x\log^2x\over T\right)\]Because $\delta=1-c_0/\log^9T$, we can set $\log T=\log^{1/10}x$ to obtain

\[\psi(x)=x+\mathcal O(xe^{-c_0\log^{1/10}x}\log x)+\mathcal O\left(xe^{-\log^{1/10}x}\log^{9/10}x\right)+\mathcal O\left(xe^{-\log^{1/10}x}\log^2x\right)\]Since $\log^{1/10}x$ grows much faster than $\log\log x$, we pick $0<c<c_0$ to unify the remainder:

\[\psi(x)=x+\mathcal O(xe^{-c\log^{1/10}x})\tag{17}\]From this expression, it is easily seen that $\psi(x)\sim x$, so the prime number theorem is proven.

Prime number theorem with remainder

The vanilla prime number theorem only gives the asymptotic relation that

\[\pi(x)\sim{x\over\log x}\tag{18}\]but it does not tell the behavior of error terms, so it is necessary for us to consider the remainder of (17). Because $xe^{-c\log^{1/10}x}$ grows significantly faster than $\sqrt x\log x$, we have

\[\vartheta(x)=x+\mathcal O(xe^{-c\log^{1/10}x})\]Now, by partial summation, we get

\[\begin{aligned} \pi(x) &=\int_{2^-}^x{\mathrm d\vartheta(t)\over\log t}=\int_2^x{\mathrm dt\over\log t}-\int_2^x{\mathrm d[\mathcal O(te^{-c\log^{1/10}t})]\over\log t} \\ &=\operatorname{Li}(x)+\mathcal O\left(xe^{-c\log^{1/10}x}\over\log x\right)+\mathcal O\left(\int_2^x{e^{-c\log^{1/10}t}\over\log^2t}\mathrm dt\right) \end{aligned}\]where $\operatorname{Li}(x)=\int_2^x{\mathrm dt\over\log t}$ is the augmented logarithmic integral. For the integral in the O-term, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \int_2^x{e^{-c\log^{1/10}t}\over\log^2t}\mathrm dt &\ll\int_2^xe^{-c\log^{1/10}t}\mathrm dt=\int_2^x{\sqrt te^{-c\log^{1/10}t}\over\sqrt t}\mathrm dt \\ &\ll\sqrt xe^{-c\log^{1/10}x}\int_0^x{\mathrm dt\over\sqrt t}=xe^{-c\log^{1/10}x} \end{aligned}\]Eventually, we obtain an asymptotic expansion of $\pi(x)$ with remainder:

\[\pi(x)=\operatorname{Li}(x)+\mathcal O(xe^{-c\log^{1/10}x})\tag{19}\]Via integration by parts, we see that

\[\begin{aligned} \operatorname{Li}(x) &={x\over\log x}+\int_2^x{\mathrm dt\over\log^2t}+\mathcal O(1) \\ &={x\over\log x}+\int_{\sqrt x}^x{\mathrm dt\over\log^2t}+\mathcal O(\sqrt x) \end{aligned}\]Due to the relation that

\[{x-\sqrt x\over\log^2x}\le\int_{\sqrt x}^x{\mathrm dt\over\log^2t}\le{x-\sqrt x\over\log^2\sqrt x}\]we conclude the error term of $\operatorname{Li}(x)$ and $\log x$ cannot be improved:

\[\operatorname{Li}(x)={x\over\log x}+\mathcal O\left(x\over\log^2x\right)\]By plugging this into (19), we convert (18) into a more precise form:

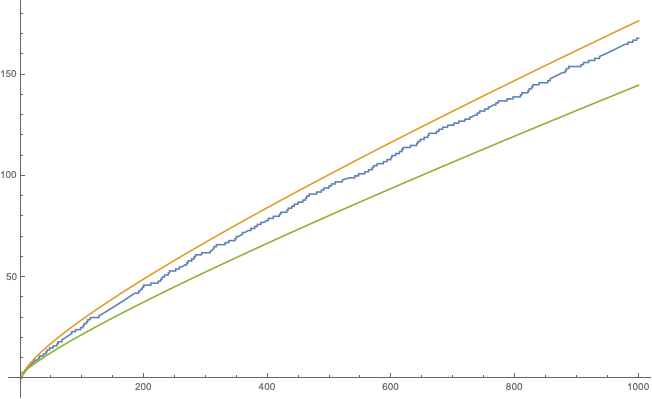

\[\pi(x)={x\over\log x}+\mathcal O\left(x\over\log^2x\right)\tag{20}\]which is another version of prime number theorem with remainder. Apparently, the error term in (20) grows much faster than that of (19), so $\operatorname{Li}(x)$ (orange) tends to be closer to the actual $\pi(x)$ (blue) compared with $x/\log x$ (green):

Conclusion

In this article, we began our proof by introducing Dirichlet series and an inversion formula. Then, we apply the inversion formula (1) to the Chebyshev psi function to obtain (2). To approximate $\psi(x)$, we estimate the remainder of (2) when $T$ is finite. Eventually, we explored some basic properties of $\zeta(s)$ in order to estimate the integral in (9). Finally, using partial summation and other elementary technique, we obtain an asymptotic formula for the standard prime-counting function $\pi(x)$ with an error estimate.

In fact, when Riemann hypothesis is true, we can improve the error bound even further, but that will require more knowledge on $\zeta(s)$'s behavior in the critical strip. As a result, we will dig further into the Riemann zeta function in the future articles.